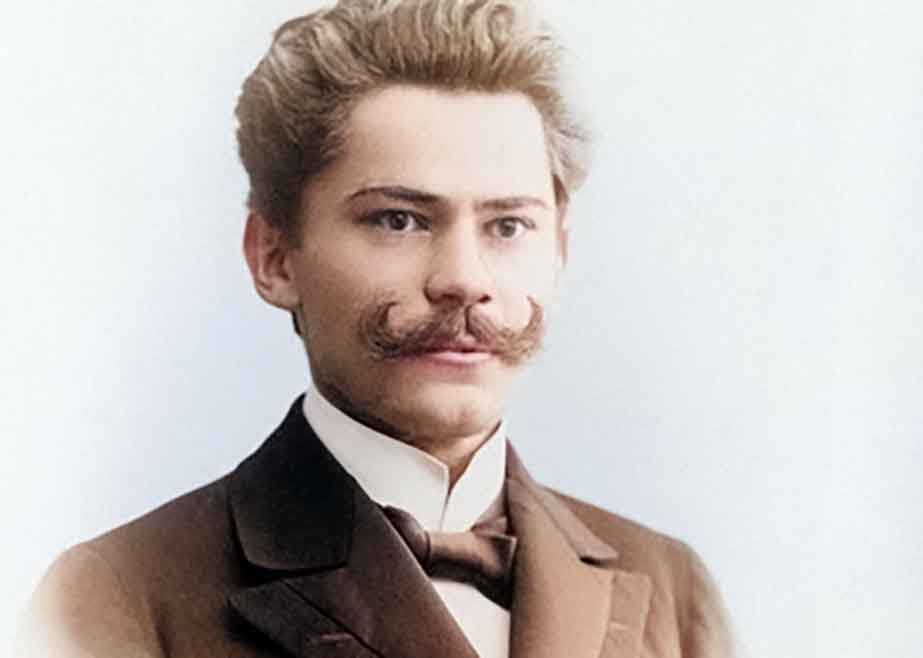

On October 28, 1845, Zygmunt Wróblewski was born, one of the most outstanding Polish physicists, a pioneer of cryogenics, who, together with Karol Olszewski, was the first in history to liquefy the gases constituting the Earth's atmosphere.

Zygmunt Wróblewski was born and educated in the borderlands of the pre-partition Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. He came from Grodno and attended his first physics studies in Kiev. His education was interrupted by the outbreak of the January Uprising (January 1863), in which Zygmunt became involved in the underground resistance. After a few months, he was arrested and imprisoned, from where, a year later, he was exiled to Siberia. His health then deteriorated. A progressive eye disease threatened blindness. After an amnesty was announced, he came to Warsaw (1869), from where he then traveled to Berlin to undergo surgery. There, he continued his education in physics.

Zygmunt Wróblewski (1845-1888) (Source: DlaPolonii.pl)

In 1872, Zygmunt Wróblewski found employment as a laboratory assistant at the University of Munich. Two years later, he earned his doctorate with a thesis on the exploration of the mechanical excitation of electricity. He then secured a position at the University of Strasbourg, where he earned his habilitation in 1876. His research enjoyed recognition and popularity among physicists of the time.

In 1880, Wróblewski traveled to France and then to England, where he visited the most important scientific centers and met leading researchers in both countries. He also continued his research, using state-of-the-art equipment. As a result, he was the first to obtain and study carbon dioxide clathrate (snowflake-like crystals made of carbon dioxide). As it would soon turn out, this was only the beginning of the achievements that would follow in the following years.

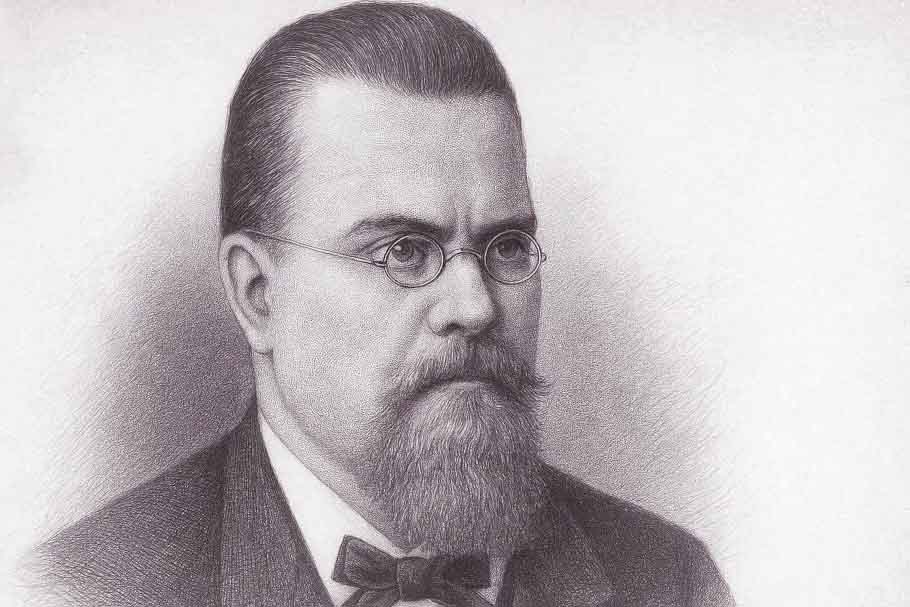

In 1882, the physicist returned to Poland, bringing with him modern equipment he had acquired in Paris, including a device for obtaining low temperatures, designed by Louis Cailletet. Wróblewski settled in Kraków, where he took up the Chair of Experimental Physics at the Jagiellonian University. He also began collaborating with another distinguished physicist and chemist, Karol Olszewski. Together, they improved Cailletet's apparatus, making it possible to conduct experiments on the condensation of gases into static liquids, a feat that had not yet been achieved.

In 1877, L. Cailletet and R. Pictet liquefied oxygen in a dynamic state, obtaining a mist that disappeared after a moment. However, this prevented further research into gases to better understand their nature. This required obtaining a static and stable liquid on which further experiments could be conducted.

The modifications Wróblewski and Olszewski made to Cailletet's apparatus allowed them to achieve a temperature previously unattainable for this type of device, –130°C (–202°F), which later allowed them to condense oxygen to a static liquid (March 29, 1883). Soon, they also condensed nitrogen (April 13) and carbon monoxide (April 16). Thus, in a Krakow laboratory—not in the capitals of the empires of the time or the most well-funded and developed research centers in Europe—two Poles achieved a breakthrough in the world of science. Until then, it had been believed that these gases did not occur naturally in liquid form. Wróblewski and Olszewski proved otherwise. From then on, they were considered not only pioneers but also world-leading experts in cryogenics.

Unfortunately, the paths of the outstanding Polish physicists quickly diverged. A few months after achieving the first-ever condensation of gases to form a static liquid, Zygmunt Wróblewski and Karol Olszewski ended their collaboration and continued their research separately.

Wróblewski attempted to condense hydrogen on his own, but the feat was unsuccessful. However, he had other significant achievements to his credit. He managed to determine the density, pressure, and temperature of liquefied oxygen, and also calculated the critical constants of hydrogen. He also solidified carbon dioxide and alcohol. His position in the world of science also grew. In 1883, he became a member of the Academy of Arts. In 1887, the Vienna Academy awarded him an award for research that had contributed most significantly to the development of physics in recent years. He also held numerous honorary and representative positions in scientific bodies.

Zygmunt Wróblewski's further scientific career was cut short by his tragic death. On March 25, 1888, a fire broke out in his laboratory, causing the physicist to suffer severe burns. Despite treatment, he died on April 16, at the age of 43.

Zygmunt Wróblewski's grave is located at the Rakowicki Cemetery in Krakow. The tombstone bears an inscription commemorating his achievements in both science and the uprising: "He suffered for his country, he died for science."

Translation from Polish by Andrew Wozniewicz.