The concept of the “Pomeranian Massacre of 1939” covers the acts of direct extermination committed against the Polish population between September and December 1939 (in some places until the beginning of 1940) by Volksdeutscher Selbstschutz units, with the active support of the Wehrmacht and the SS.

It was a planned, massive operation carried out in over 400 towns located in the pre-war Pomeranian Voivodeship [a province in the north of Poland], in which the Germans employed special killing techniques. The victims were Polish citizens of Polish and Jewish ethnicity, as well as representatives of various social classes: intelligentsia, clergy, workers and landowners, and the mentally ill.

The term “Pomeranian Massacre of 1939” had not been used in scientific literature until recently. The terms “bloody Pomeranian autumn”, “pogrom” and “German Katyn 1939” were used more commonly, as well as “Intelligenzaktion” and “Säuberungsaktion”, which were used by the perpetrators.

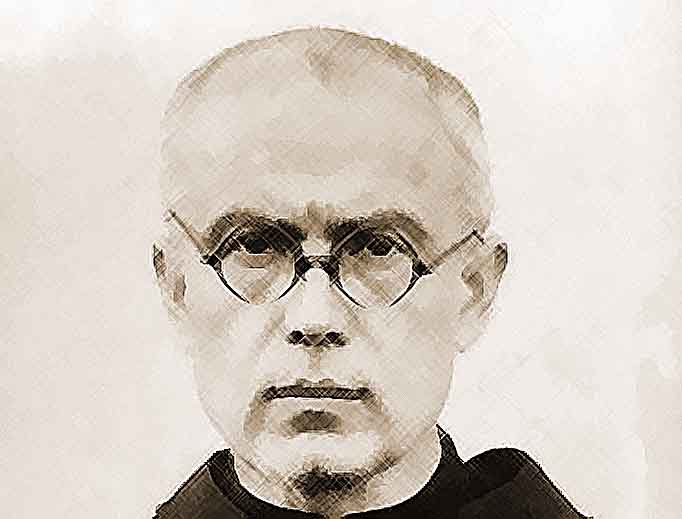

Fordon near Bydgoszcz, October 1939. The headmaster of the Stefan Batory Elementary School in Bydgoszcz, Czesław Lorkowski, just before being shot by the Germans in the “Valley of Death” near Fordon (Source: Institute of National Remembrance Archives)

Greater Pomerania in the Second Polish Republic

As a result of the provisions of the Treaty of Versailles, Gdańsk Pomerania returned to the recently reborn Second Polish Republic, and on August 1, 1919, the Pomeranian Voivodeship was established. The Polish state began the reconstruction of the local administration and other local governing structures in the area that had been part of Prussia for over a century. However, local Germans continued to strengthen their position by creating political parties, mainly the Young German Party (Jungdeutsche Partei, this one already in the 1930s).

German propaganda calling the Pomeranian Voivodeship the “Pomeranian Corridor”, separating the Weimar Republic (and later the Third Reich) from East Prussia, was also significant. The Germans considered the western territories of the Second Polish Republic to be native German lands, which is why the main goal of the German occupier was their "de-Polonisation" (Entpolnisierung), and the primary method used for this purpose was genocide.

Even before the Wehrmacht troops entered Poland, members of German parties, in cooperation with the Volksdeutsche, prepared proscription lists with the names of Poles who were to be arrested. The Special Search Book for Poland (Sonderfahndungsbuch Polen) was also meticulously updated, containing the personal data of citizens of the Second Polish Republic who were wanted by the German authorities for their independence or social activities. In the first weeks of the occupation, officers of the security police, analysing denunciations from the Germans living in Poland before the war and documentation left behind by the Polish authorities and Polish organisations and associations, began to create lists of those who opposed the new government.

Volksdeutscher Selbstschutz in Pomerania

In the administrative area of Gdańsk Pomerania, which from October 26, 1939, constituted the Reich District of Gdańsk-West Prussia, the Germans committed mass crimes until April 1940. The governor of the Reich District of Gdańsk-West Prussia, Albert Forster and his local administration, whose goal was to completely Germanize Pomerania within 5 years, played the main role in the extermination of the Pomeranian population. In the Free City of Gdańsk, even before the outbreak of the war, the Germans established the SS-Wachsturmbann Eimann assault and guard unit, which participated in the extermination of the Polish population and the mentally ill in the Kartuzy, Kościerzyna, Starogard and Wejherowo counties. Local Germans operating under the supervision of the SS also played a special role in the terrorsystem in Gdańsk Pomerania.

Even before the Wehrmacht troops entered Poland, members of German parties, in cooperation with the Volksdeutsche, prepared proscription lists with the names of Poles who were to be arrested.

At the beginning of September, local units of the German citizen guard consisting of German Volksdeutsche began to be formed in Gdańsk Pomerania. They were directly subordinate tothe so-called Ortsgruppenleiters. They were only formally defensive in nature, but in fact they were used to settle personal scores with Polish neighbours. In connection with this, the “Pomeranian Massacre of 1939” is also often referred to as the Neighbourhood Massacre. Itis important to mention that the victims and perpetrators often knew each other. For example, Albert Hebel was murdered in the forest between Świecin and Wejherowo on October 9, 1939, and his wife Frieda Hebel, interrogated in 1970, testified in the following way:

The perpetrator of my husband's arrest was Heinz Till, who was angry with my husband because my husband had given incriminating testimony against Till to the Polish authorities in the spring of 1939. This was in a case in which Till had been arrested and then released in September 1939 by the invading German army.

After a summit held at Hitler's headquarters between September 8 and 10, 1939, Heinrich Himmler decided to merge the existing local organisations and establish the Volksdeutscher Selbstschutz. The organisation was established across all of occupied Poland, but it played a special role in the Pomerania province. Ludolf von Alvensleben “Bubi”, Himmler's former assistant, became its head. The Reichsführer SS treated Selbstschutz as a substitute for Einsatzkommando, serving to de-polonize German lands. Over 38,000 local Germans joined the organisation in Pomerania, meaning almost all men aged 17 to 45. One of the volunteers was Jan Dzionk, a resident of Kartuzy, who testified years later:

In September 1939, right after the German army occupied Kartuzy, they hanged posters calling for people to join the Selbstschutz. I didn't know who signed them. I also joined the Selbstschutz. I went to a Selbstschutz meeting for the first time in September 1939. […] I conducted these exercises on Hauptke's orders. I was a sergeant in the German army during the First World War, so I knew military drill. I conducted these exercises every Sunday for two months. After two months, I was released from the Selbstschutz.

Arrests and Executions

The inhabitants of Polish towns and villages were dragged out of their homes by force at night and taken to makeshift prisons and jails. The places where future victims were gathered were most often the buildings of old factories, the basements of schools, cells at police stations, churches and castles. The scenario was always very similar to that of the family of Józef Bronek from Tczew, who were arrested on November 1, 1939:

From the house we had left, the Germans escorted me and my family to the “Arkona” factory in Tczew, where the Germans immediately ordered us to get on trucks. Then, together with other arrested people who were there, me and my family were taken to the castle in Gniew, where about 200 people were already imprisoned: men, women and children. […] I saw more than once how all the guards I mentioned beat the detained peoplewith the butts of their rifles, their fists and kicks. I was also beaten at the castle in Gniew by a guard called Ligman for no apparent reason. During my imprisonment in the castle in Gniew, 60 people, men, women and children, slept on a pallet, on the floor without beds, in a room measuring 12x12 metres. I stayed at the castle in Gniew with my family from November 1 to December 13, 1939. During this entire period, the Germans did not give us any food and we managed to survive only thanks to the generosity of the local people of Gniew.

In the detention centres and camps, detainees were grossly mistreated, and in some cases, the guards also set up execution sites where they killed prisoners. People's courts (Volksgericht), sometimes called Selbstschutz courts (Selbstschutzgericht), referred to by Poles as Mordkomission, held their sessions in the detention centres. These courts, following Nazi ideology, issued orders to murder individual prisoners with complete impunity, without any evidentiary proceedings. The commission, analysing the proscription lists, freely decided on the fate of the arrested person. They could be shot, sent to a concentration camp or released on a whim.

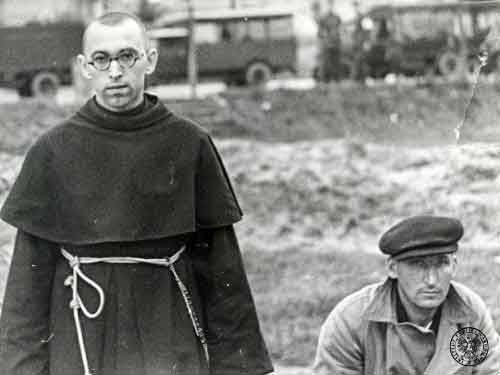

Gdynia, September 14, 1939. Two residents interned by the Germans, shortly after the occupation of the city, are waiting for questioning in the square on Świętojańska Street. On the left stands a monk from Niepokalanów dressed in a dark robe: Brother Kornel - Władysław Kaczmarek (Source: Institute of National Remembrance archives)

Most of the victims of the Second World War in Pomerania did not die in concentration camps or as a result of military operations, but were shot in death pits. Poles were transported from detention camps and prisons to execution sites. According to the guidelines of the Reich’s Security Main Office (RSHA), execution sites were to be located near large cities with prisons, and from where it was easy to transport convicts by truck or train, and at the same time they were to be located far from human settlements in forest areas that muffled the sound of gunfire well.

At the beginning of September, local units of the German citizen guard consisting of German Volksdeutsche began to be formed in Gdańsk Pomerania. They were directly subordinate to the so-called Ortsgruppenleiters. They were only formally defensive in nature, but in fact they were used to settle personal scores with Polish neighbours.

The places of mass executions in Pomerania were located in gravel pits and sand pits (Paterek near Nakło nad Notecią, Mniszek), vast valleys and forest ravines (Fordon in Bydgoszcz, Płutowo), anti-artillery ditches and rifle trenches (Tryszczyn, Fordon, Pola Igielskie near Chojnice). According to RSHA guidelines, most executions took place in forests near larger towns (Piaśnickie Forests, Szpęgawskie Forests, Hopowskie and Mestwinowskie Forests near Kościerzyna, Skarszewskie Forests, Kaliskie Forests near Kartuzy, Barbarka near Toruń, Pińczata Forest near Włocławek, Kujawski Forest and Rybienieckie Forest near Klamer, Brzezinka Forest near Brodnica, Karnkowskie and Radomockie Forests near Lipno).

Executions were also carried out in city parks (Łasin, Grudziądz, Chojnice, Kcynia), in Gestapo and Selbstschutz prisons and camps (“House of execution” in Rypin, artillery barracks in Bydgoszcz), in fields belonging to Polish and German farmers. In Karolewo (Sępolno district) the execution site was a clearing where sports competitions and political rallies were held before the war. Jewish cemeteries (Skarszewy on Lake Borówno, Bydgoszcz, Świecie, Szubin, Wyrzysk, Łobżenica, Kcynia, Włocławek) and Roman Catholic cemeteries (Bydgoszcz, Nakło nad Notecią) were also places of execution.

Szubin, October 21, 1939. Just before the execution. Two SS officers (one of them SS-Sturmbannführer Ernest Tiedemann) read the death sentence to a group of Poles (Source: Institute of NAtional Remembrance archives)

Sometimes, the local population witnessed the executions by accident. Feliks Węsiora, who lived in Hopowo, a village in the Kartuzy county, during the war, could clearly hear the shots coming from the nearby forests:

In the autumn of 1939, one day, when I was raking leaves with my wife in the forest near Sarni Dwór, Kartuzy county, I heard shots from automatic weapons and other firearms coming from nearby. After some time, Fryderyk Triebull, who lived in Nowy Dwór, Kartuzy county, approached me, dressed in civilian clothes, with a green armband on his left hand, and ordered me and my wife to leave the forest immediately, because supposedly military exercises were taking place there. I went home immediately with my wife. The next day, from various people whose names I no longer remember, I learned that the Nazis had shot about 40 Poles in the forest in Sarni Dwór, while my wife and I were in the forest raking leaves.

The process of erasing the traces and the activity of Sonderkommando 1005 in Pomerania

As the Eastern Front approached the borders of the Reich, so came the process of erasing the traces of the massacres. In 1944, Sonderkommando 1005 operated in Gdańsk Pomerania. Its task was to destroy the evidence of crimes committed by police and SS units and to cover up mass graves before the Red Army entered. During that time, they exhumed the bodies of people murdered in 1939 from nearly 30 mass execution sites and burned them. In some places of mass execution, such as Piaśnica near Wejherowo, despite years of research, the activity of a special commando has not yet been confirmed. In the Piaśnica Forest, SS and police units used 36 prisoners from KL Stutthof, known as the “commando to heaven”, to extract and burn the bodies. The operation lasted about seven weeks. Upon its completion, the prisoners were also murdered and their bodies burned as well.

Interrogated as a witness in 1946, Jan Angel testified:

In the autumn of 1944, when smoke was rising over the Piaśnica state forest, one morning, while riding my bike to work along a forest road, I noticed five people walking to section no. 107. They were two gendarmes and three prisoners. These prisoners were dressed in grey trousers and blouses with purple stripes. I did not notice whether they had caps on their heads, because I focused my attention on their legs, which were in chain shackles. The chains were short, so the prisoners took small steps. One gendarme walked in front of the prisoners, and the other one behind them. These prisoners had nothing on them. They were probably heading to section 107 to prepare the wood, because from this section we could hear the sounds of sawing and pricking the wood, working there. We were working at one end of this section, and the sounds came from the other end, i.e. from a distance of about 800 (eight hundred) meters. We, the workers, reasoned that these prisoners were burning the bodies of those murdered in the local forests, which were being dug out of their graves. It was commonly said in our group of workers that these prisoners were from the Stutthof camp.

Since 1946, on the initiative of members of the local structures of the Polish Western Union and the Commission for the Investigation of German Crimes in Poland, special exhumation commissions were established to determine the number of victims murdered in 1939 in individual mass execution sites. Moreover, local press systematically published articles about the discovery of mass graves, at which time families would come to these places to identify their loved ones. During the identification of the bodies, carried out with the participation of the families of the murdered victims, it was possible to establish the personal details of some people. The bodies of some of the recognised victims were taken away by their families and buried in family cemeteries, while others were reburied in mass graves at the execution sites.

After the end of the Second World War, the countries of the anti-Hitler coalition recognised mutual assistance in prosecuting and punishing war criminals guilty of murder and abuse of the population of the occupied countries as one of their main goals. Since then, the prosecution of such crimes has become a permanent part of the practice of justice in various national legal systems.

Most of the perpetrators of the Pomeranian Massacre of 1939 were not found after the war and were never fairly tried. Investigations conducted since the end of the 1940s by the District Commission for the Investigation of Nazi Crimes in Gdańsk were suspended in the 1970s due to the inability to question witnesses and suspects living in the West, where it was difficult to reach them at that time. Since 2000, when the Institute of National Remembrance was established, investigations into the crimes committed in 1939 in Pomerania have been successively undertaken and legally concluded at the Branch Commission for the Prosecution of Crimes Against the Polish Nation in Gdańsk and the Delegation in Bydgoszcz.

Lubawa, December 7, 1939. Members of Selbschutz Westpreussen shoot Poles lined up against the wall (Source: Institute of National Remembrance archives)

The scale of the massacres in Gdańsk Pomerania in the autumn of 1939 was the largest at that time in all of occupied Poland. It was also the first such large-scale extermination of civilians. Polish historians estimate that in 1939 the Germans murdered between 20 and 40 thousand people in Gdańsk Pomerania. To date, nearly 10 thousand victims have been identified by name and surname. Lists with the established surnames of those executed constitute evidence of investigations conducted by the Branch Commission for the Prosecution of Crimes Against the Polish Nation in Gdańsk and the Delegation in Bydgoszcz.

Unfortunately, the memory of the victims of the Pomeranian Massacre of 1939 is cultivated only on a local level. The “Piaśnicka Family” Association, which operates in Wejherowo, takes care of the graves in Piaśnica and is involved in the organisation of ceremonies in honour of the murdered, which take place every year in the Piaśnica Forests. On the initiative of the Association and Father Daniel Nowak, part of the church of St. Christ the King and Blessed Alicja Kotowska in Wejherowo was named the Piaśnica Chapel. In the Szpęgawskie Forests, in 2019, a new monument was unveiled to commemorate the murdered, 2,400 of whom were identified by name and surname. In Toruń, in October 2018, the Monument to the Victims of the Pomeranian Massacre of 1939 was unveiled in the city centre, the capital of the pre-war Pomeranian Voivodeship. The monument, symbolising an abandoned house to which its inhabitants will never return, has around 400 names of places where Pomeranian citizens of the Second Polish Republic were murdered.