John Paul II quickly won the hearts of people around the world. And just as quickly, he became the terror of communist apparatchiks, who saw him as a deadly threat to their power.

“Oh my God!” exclaimed Edward Gierek, then the number one man in the communist government in Poland. It was the evening of October 16, 1978. Gierek had just heard from Stanisław Kania, one of his close associates, that the College of Cardinals in the Vatican had elected Karol Wojtyła pope.

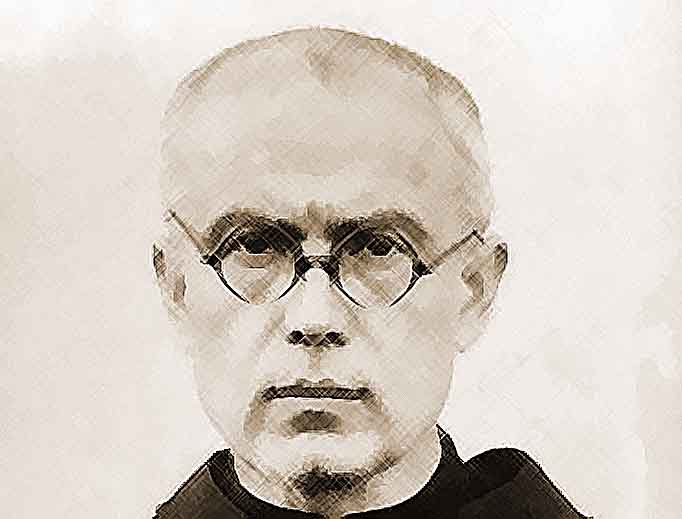

Karol Wojtyła as Pope John Paul II (Source: Wikipedia)

In Krakow, where Wojtyła was archbishop, crowds were already spontaneously gathering in the Main Market Square. Widespread rejoicing spread to other cities as well. For the communists – who viewed the Church as an enemy and a threat – this did not bode well. Opening the Politburo meeting the following day, Gierek openly declared: "Comrades, we have a problem." Perhaps even he, however, did not anticipate what a major problem John Paul II would prove to be for the entire Eastern Bloc.

Lenin's Denied Testament

"Religion is the opium of the people," Karl Marx proclaimed in the mid-19th century. Vladimir Lenin echoed these words decades later. In the totalitarian Soviet state, striving to control every aspect of its citizens' lives, constitutional freedom of religion served as a cloak behind which concealed a ruthless, even obsessive, fight against Christianity. With similar ruthlessness, the Soviets engaged in the fight against the Church in the Polish eastern territories, seized in 1939 under the terms of the pact between Joseph Stalin and Adolf Hitler.

At the same time, the Germans were brutally cracking down on the Church in occupied western and central Poland. As a result, one in five Polish clergy died during World War II. "But the rest remained. Many. I won't let them act, think, breathe," assures Julian Kordek, an officer of the communist secret service, in the feature film Karol. The man who became pope.

The year is 1946. Young Wojtyła is ordained a priest, and in postwar Poland – handed over by the Allies to the Soviets – the fight against the Church begins anew. And although Kordek is a fictional character, the film faithfully depicts the communists' methods. Priests are imprisoned, Primate Stefan Wyszyński is interned in 1953, and Wojtyła is surrounded by secret police informants. The repression is intended to break the Church and the spirit of Poles.

This calculation proved ineffective. The Millennium celebrations of Poland's baptism in 1966, preceded by a long-standing program of the Great Novena, clearly demonstrated that the nation refused to be intimidated or secularized, and that the Catholic Church remained a powerful and truly independent institution. Despite the government's obstacles, hundreds of thousands of Poles participated in religious ceremonies.

Another milestone on the road to national awakening was John Paul II's first pilgrimage to his homeland in June 1979. Just a few months earlier, during the solemn inauguration of his pontificate, the Pope had uttered the significant words: "Do not be afraid!", addressed to the entire world, but particularly important as a message to societies behind the "Iron Curtain." During a homily delivered later in Warsaw, at what was then known as Victory Square, John Paul II uttered yet another invocation, one that also went down in history: "Let Your Spirit descend and renew the face of the earth. This land."

The Pontificate That Changed the World

This desire, expressed on June 2, 1979, materialized less than a year later. A strike broke out in August 1980 at the Gdańsk Shipyard – then named after Lenin – and quickly spread throughout Poland. Thus was born the Independent and Self-Governing Trade Union "Solidarity" – a nearly ten-million-strong social movement independent of the communist authorities. John Paul II supported "Solidarity" from the outset, and in January 1981 he received its leaders at the Vatican.

Dark clouds once again gathered over Poland's path to freedom. In May 1981, Mehmet Ali Ağca severely wounded the Pope. Much suggests he acted on orders from Bulgarian communist secret services—and that the inspiration came from Moscow. In December of that same year, Wojciech Jaruzelski, the newly elected General Secretary of "People's" Poland, imposed martial law to deal with Solidarity once and for all and save the Red regime.

But the avalanche of freedom, once unleashed, was unstoppable. In June 1983, John Paul II's second pilgrimage to his homeland buoyed the democratic opposition and rekindled hope in the hearts of Poles. The communists were helpless. "We can only dream now that God will call him to his bosom as soon as possible," said Interior Minister Czesław Kiszczak, Jaruzelski's right-hand man, about the pope at the time. Fortunately, this dreadful dream did not come true. The actions of the communist secret services, which were bent on neutralizing the Vatican's influence, also yielded little results.

John Paul II's pontificate changed the face of more than just Poland. His Eastern policy—emphasizing a consistent commitment to human rights—also bore fruit in Soviet Ukraine and Lithuania, Czechoslovakia, and other Eastern Bloc countries. It fostered religious and national revival, strengthened dissident circles, and undermined the foundations of the communist system. It perfectly complemented the actions of US President Ronald Reagan, who openly challenged the "evil empire."

Tangible effects appeared in the late 1980s. In Poland, the June 1989 elections gave Solidarity a landslide victory, but for the communists they were a disaster, from which they were unable to regain the initiative. Soon, the Autumn of Nations brought democratic changes throughout the Soviet "external empire." Finally, in 1991, the USSR itself collapsed.

The Return of History

However, political scientist Francis Fukuyama, who predicted the end of history at the end of the Cold War, was wrong. Under Vladimir Putin's rule, Russia's political and military elites are gradually striving to rebuild the empire. John Paul II has been gone for 20 years. But in these difficult times, we can still draw on his spirit.

Translation from Polish by Andrew Wozniewicz.